July 20

This day’s lecture was on the period of Soviet occupation in Lithuania. Interestingly enough, it was given by an American grad student from the University of Washington who doesn’t have an ounce of Lithuanian blood. She’s a history major specializing in Russia and eastern Europe who just fell in love with Lithuania once she began to study the country. She’s been here nearly a year on a Fulbright, and is doing research for her dissertation on Kalantines, the events surrounding the immolation suicide of Romas Kalanta in Kaunas in 1972 as a protest aginst Soviet repression.

Lithuania during its brief independence didn’t have a hugely sophisticated government with many alliances and was ripe for the picking when Germany and Soviet Russia signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939 dividing up Europe. Lithuania was forced to create a Soviet friendly government, and its president fled. Over two days in 1941, 34,000 people were deported, many to Siberian prisons. My grandmother’s nephew was among this first wave of deportees, as he was both a doctor and an officer.

The Soviets’ plan to deport many more was put on hold for four years when Germany violated the treaty and occupied Lithuania from June 1941 to July 1944 and murdered 95 percent of Lithuania’s Jews. When Stalin regained Lithuania In 1944, he continued deportations of more than 100,000 Lithuanians to the far reaches of Siberia, many inside the inhospitable Arctic Circle and some so close to Alaska that they actually believed that they might be taken to America. Collectivization of farms and placement of Russian people into Lithuanian homes followed the deportations. Up until almost the time that Stalin died in 1953, Lithuanian men and women were involved in the Partisan movement, called the Forest Brothers, waging guerilla warfare against the Soviets.

Relaxation of repression under Kruschev eliminated extreme Stalinist terror, allowed the return of many deportees (including my relative), and opened some foreign contact. Kruschev’s ouster in 1964 crushed much of the renewed Lithuanian nationalism, but people had seen the rest of the world through the crack in the door and western ideals kept seeping in. Kaunas became a hotbed of teen rock bands in the late ’60s, even though jeans and long hair were forbidden. The city mobilized after Kalanta’s protest suicide, and held unheard-of public marches.

Dissent kicked into high gear from 1974 to 1986. The Catholic Church publicly opposed the Soviet regime; human rights dissidents supported the Helsinki Accords and Lithuania churned out more underground publications per capita than any other part of the USSR. Of course, this landed many people in the gulags. But the time Gorbachev came into power in 1986, it was only a short time until the occupied countries took glasnost and perestroika much farther than he had intended. Instead of wanting to make a better Soviet Union, Lithuania worked toward independence in 1990.

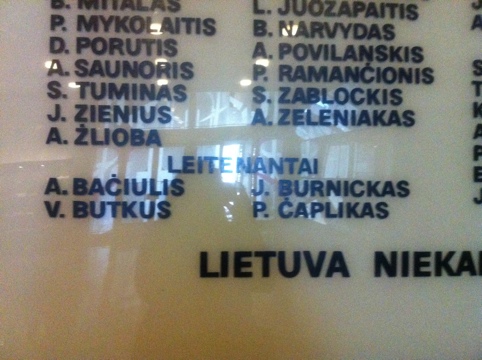

Our afternoon trip was to IX Forto (Ninth Fort), which was originally intended as a Russian defense against invaders, but was abandoned by the Russians in their retreat during WWI and was subsequently used as a Lithuanian prison, a Soviet prison and eventually a Nazi prison and execution site for more than 5,000 of Kaunas’s Jews. The museum there commemorates those who were held there and those who died there. I found the name of my grandmother’s nephew, A. (Alfonsas) Bačiulis, on a listing of those Lithuanian army officers who had been held there before being exiled. The fort itself is a cold, wet, haunting place with dank cells and dark corridors. I felt deeply for those who were never able to escape its hold, and was grateful for the sunlight that greeted us at the end of the tour.

Back at the dorms, I finally got the laundry key and rushed to do two loads before meeting the rest of the group at at the Magnus Hotel for a drink and panoramic view of the city. Even after 40 minutes of drying, my clothes were still so wet that I used every available means of hanging them to dry around the room, including doors, chairs, desks, doorknobs and window handles. The people bringing the refrigerator up tomorrow will certainly get a full appreciation for my wardrobe tastes.

Next: A taste of village life

Dear Terese,

With great curiosity I follow the events of your Lithuanian summer. I must say it’s really interesting to see at least some aspects of my homeland through your eyes. As for this post, I would just like to enter one correction – Romas Kalanta set himself on fire not in 1967, but in 1972. I was already 13 years old then and have some dim memories of that spring. Way too little, regretfully.

Diana,

Thank you so much for the correction. And I welcome any future fact checking! I was a little hesitant to write about historical events because I know that I’m apt to get some facts wrong with the whirlwind education we’re getting in the Refresh course, but I’m finding it all so interesting because I knew so little about the period and the motivations.

I know I’m just scratching the surface of the country with my posts, but I have a growing appreciation for Lithuania every day that I’m here.